Portrait in Nineteen Bags

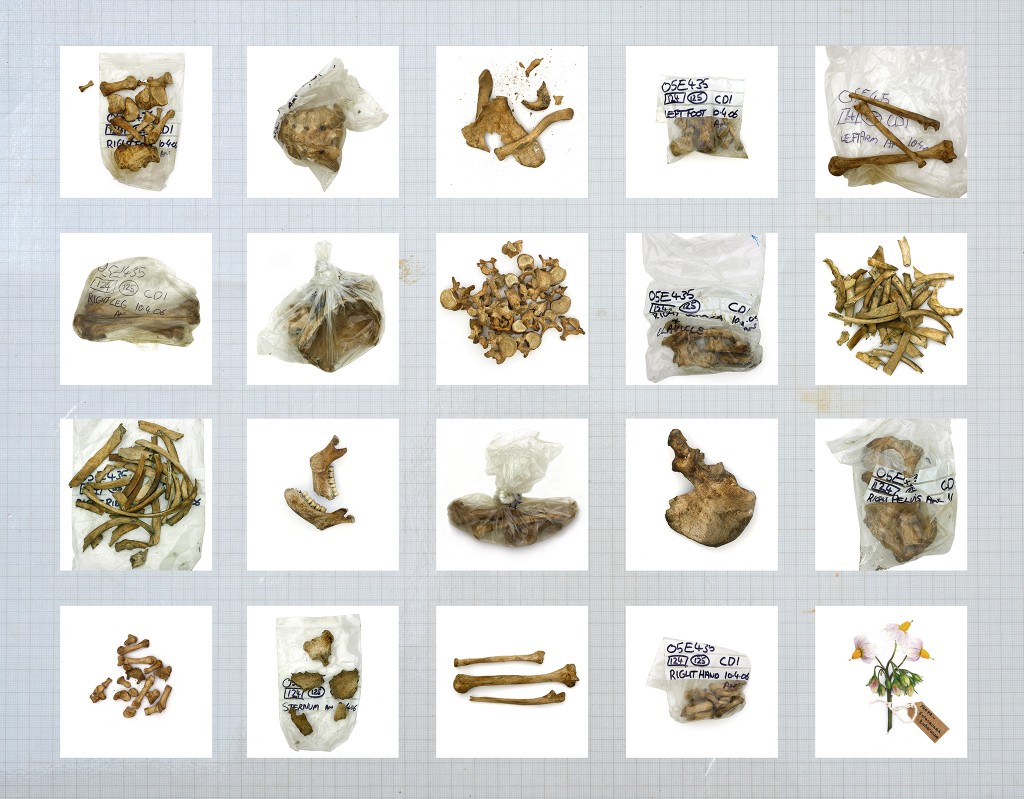

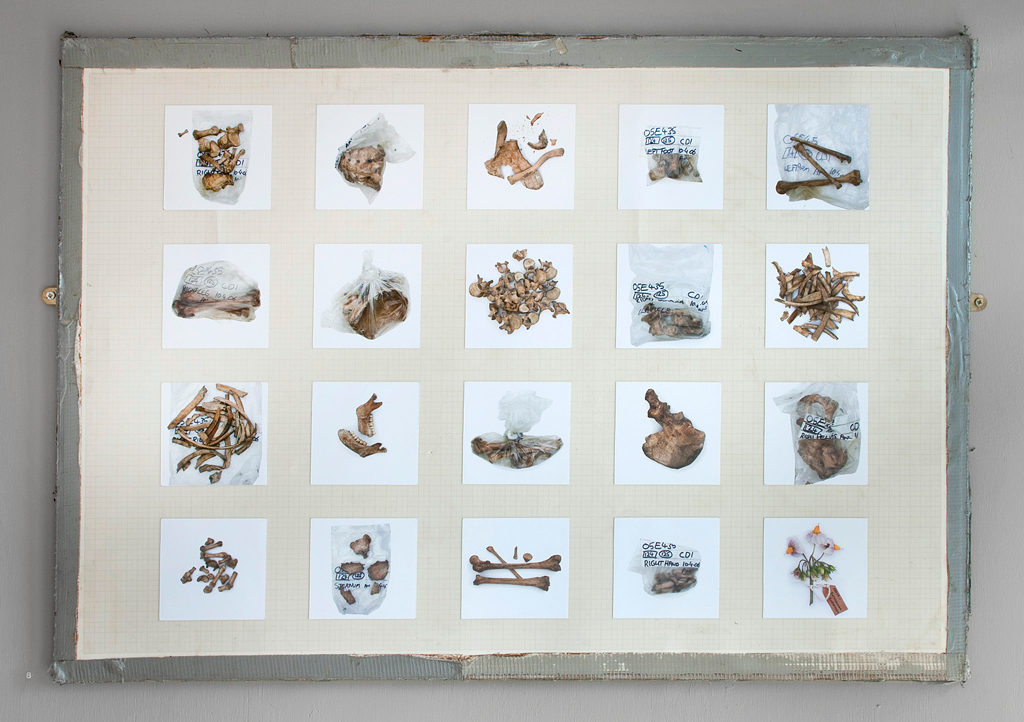

Portrait in Nineteen Bags is a conceptual piece that investigates the representation of human remains in science and the museum. It is a single artwork made up of twenty photographs arranged in a grid. There are three versions, one, above, is designed for screen viewing only, whilst Version 1 is a large gallery piece with each photograph in a box frame and arranged in a grid on the wall, and the third piece (Version 2 ) has each image mounted on an archaeological planning board (A1 in size).

Nineteen Bags is a reference to the division made by archaeologists of the human body during the process of excavating articulated human skeletal remains (hence the display of the parts of a disarticulated skeleton, as artefacts in a grid). The twentieth image, on the bottom right, is a potato flower, as in this case the skeleton was from a famine grave excavated from the site of the Kilkenny workhouse in 2006. The person depicted here was a male, who died aged between 25 to 35 years old. Skeletal evidence indicates he was a clay pipe smoker. He died as a result of the Irish famine due to the failure of the potato crop in the 1840’s. This is all that is known about the individual discerned by analysis of his remains and the situation of his exhumation.

The following is the osteologist report on the remains;

Skeleton number: CDI

Pit: [124]; (125)

Completeness: 98%; Complete skeleton.

Preservation: Very good

Age: 25-35 years (Early middle adult)

Sex: Male (+1)

Stature: 159.56 ± 3.85cm

Position:

Dental inventory:

| MAC | DCC | ||||||||||||||

| 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13* | 12* | 11 | 25* | 26 | 27 | 28 | |||||

| 48 | 47** | 46** | 45* | 44* | 43* | 42 | / | / | / | 33* | 34* | 35* | 36 | 37 | 38 |

* Clay-pipe facet ** Foramen caecum

Dental pathology: Caries (2/29), slight calculus

Skeletal pathology: A button osteoma (8mm) on the mid-superior part of the left parietal bone, 18mm from the mid-sagittal suture. Osteophytes and porosity on the articular processes of T4-T5 and T8. Minor ligamentum flavum on T5-T12. Slight to moderate Schmorl’s nodes on the bodies of T7, T11-L1 and L3-L4. An area of healed infection on the distal half of the popliteal surface on the right femur (50x29mm) with sclerotic irreggular new bone formation with two moderately shallow fossae. Possibly well healed osteomyelitis.

Metrical indices:

Non-metric traits and anomalies: Bilateral lambdoid ossicles, unilateral mastoid foramen exsutural (left), bilateral acromial articular facet, bilateral the vastus notch, bilateral anterior calcaneal facet double, unilateral peroneal tubercle (left), unilateral atlas facet double (right) and transverse foramen bipartite C5.

This work was made in 2007. The remains were subsequently re-interred in consecrated ground in 2010 with a religious ceremony. With thanks to Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd., for allowing access to the remains and to Jonny Geber, the osteologist who’s report is reproduced above.

Background to the work

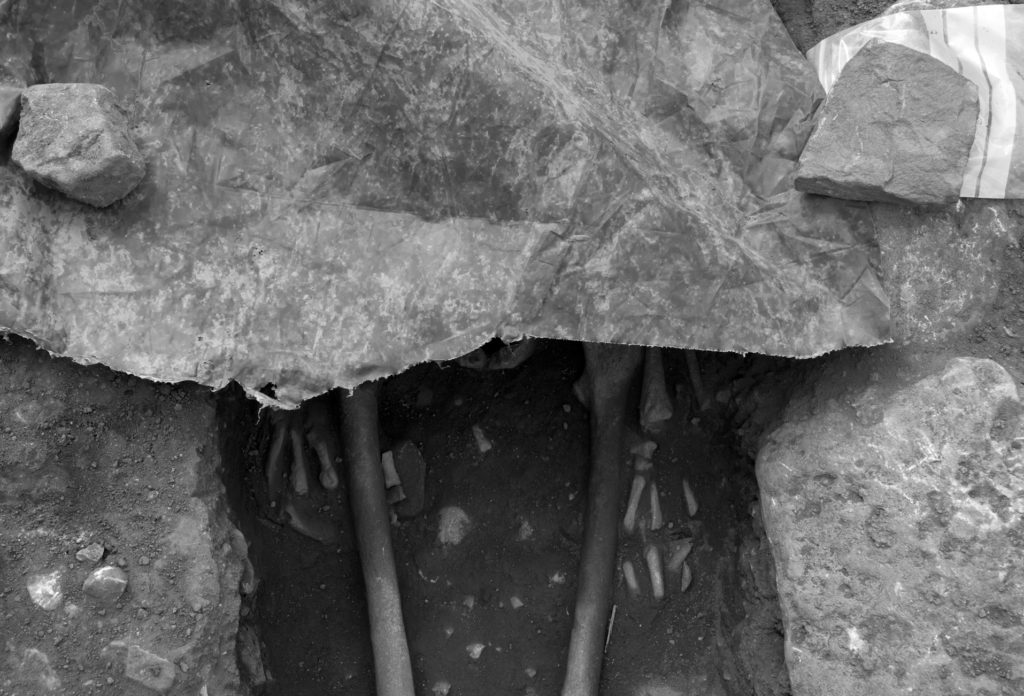

In Ireland, when a grave is excavated or a body discovered by archaeologists, the skeleton is gradually revealed for the first time since burial. The surrounding soil is removed meticulously by hand, the skeleton recorded and then removed from the grave.

Archaeologists drawing and recording remains before removal

The body is placed in bags according to the parts of the body to facilitate osteological study in the laboratory. This division and dismemberment of the skeleton results in a total of nineteen bags relating to the legs, hands, skull and so on, of the individual. Each set of bags is placed in a box and removed from site, transported to the laboratory for further analysis.

This work is a meditation on this process. The piece Portrait in Nineteen Bags is the result of both experiences of exhumation and a long journey of photographic investigation into how the experience brings up questions that can be interpreted through photography, about the rights and wrongs of representing the dead, as well as their excavation and analysis.

Initially I found that the photography of human skeletal remains during the process of excavation difficult. It was hard not to over-dramatize the subject, creating unwanted references that verged on fictional horror genres. Rather my interest lay in the process of exhumation and the relationship of the excavator to the person being excavated, whose remains are the only evidence of a life lived in the past.

After much experimentation on site, I decided to move into the laboratory to photograph the bags and the bones themselves. The reason for this was that the body, through excavation and analysis, becomes a cultural artefact, as well as a human being. Each part of the body was photographed at least three times, in the bag, on the bag and without the bag all together.

Once rendered into an artefact the body is subject to empirical analysis. Evidence is gathered from the remains about the individual’s life (see above). The rigour of this process has, as a consequence, the tendency to remove or minimise the potentially disturbing emotional responses that those undertaking the process may have to dealing with the dead. The gathering of factual evidence tends to inhibit more imaginative responses that may contradict findings, or make the work of excavation difficult to undertake.

In the course of my work as an archaeologist, I have on numerous occasions excavated human remains, I found it a disturbing experience despite the rigour of process, hence this response. I have wondered and still wonder if archaeological and osteological empiricism alone are appropriate responses to the exhumation of human remains. This process frequently does not occur in the isolation of archaeological research, but often to remove the remains from a construction site. This is understandable, as humans have been buried for a long time and grave sites are relatively common, sometimes their locations are initially (prior to excavation) unknown. The information gained from excavating these sites must be balanced, placed within the context of the retrieval of the remains and appropriate treatment given to the remains uncovered on a case by case basis (the individual photographed in nineteen bags was suitably reinterred, see above).