Introduction

Land~Edge is an investigation of my local coastline as a bioregional limit, as the edge of my inhabited space. The project examines coastlines as holistic spaces, rather than concentrating on a particular aspect, such as plastic pollution, or sea rise. This is a deliberate reflection on the way that these liminal thresholds are encountered, full of complexities and replete with potential multiple narratives.

I was working on this project during and after the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom. This political turmoil has impacted on this work as I began to consider what national identity meant in general and in particular, to me, as an English person living in Ireland and working across Europe, I have become sceptical of the idea of allegiance to a nation state, whose borders are often arbitrary and subject to change. Do I belong anywhere? yes, to the landscapes I inhabit, to places I build relationships with, but not necessarily with nations. Hence I was looking for a real border, a bioregional edge, rather than a politically defined (and policed) national boundary.

The work has three stanzas. The first part, The Search for Sisysphus is now complete and is shown below. Of the other two, The Fall and Sisyphus Found are both currently being worked on, and initial works can be found below.

{1} The Search for Sisyphus

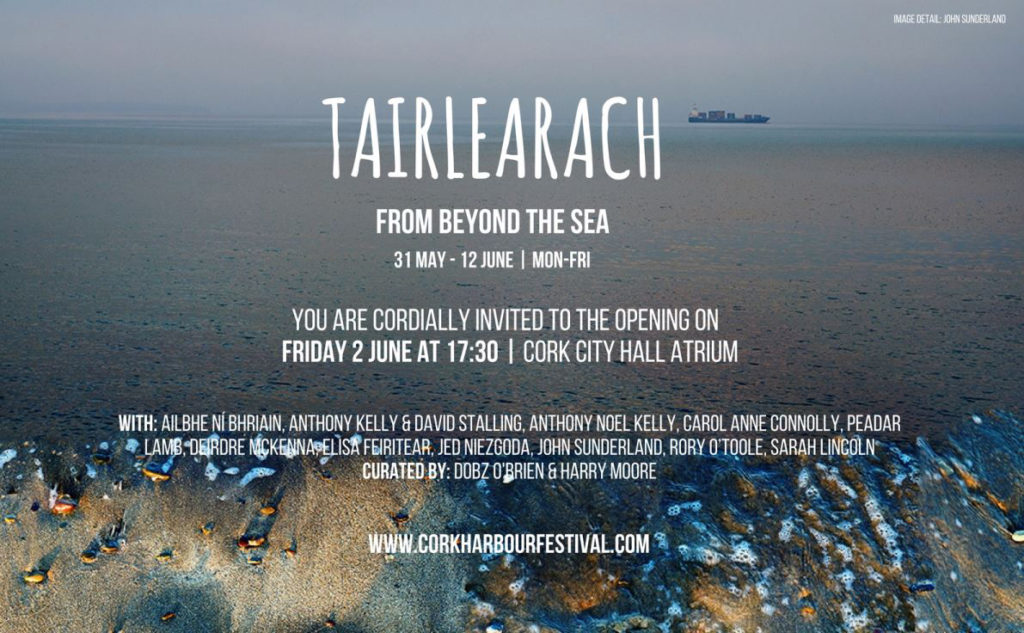

Some of the work has been exhibited at the Cork City hall, as part of the show, Tairlearach – from beyond the sea (May-June 2017) in the Cork Harbour Festival.

It was also exhibited at the Glucksman Art Gallery as part of the Conference of Irish Geographers at University College Cork in May 2017. The following artist statement about the work was published in the conference catalogue;

Land~Edge artist’s statement

At a time when physical and artificial barriers to movement are being constructed, both in America and at the edges of the European Union, and the allegiances to the EU are being debated, voted on and changed, I started to question what an actual border is and what might be a better way of considering the boundaries of the environments we occupy. National boundaries can and do change over time; they are symbolic and political. My interest lies in asking what are the persistent borders, or the edges of land, that transcend national and political identities and what could be learnt from considering these edges?

This research and practice is ongoing, but the answer so far lies in the concept of bioregionalism, or as Richard Evanoff states; “I prefer the term biocultural region, which designates a local geographic area in which specific human cultures develop in relation to the natural ecosystems they inhabit.” In terms of the edges of these regions, they are defined by physical geographical and ecological factors, rather than purely cultural considerations. They are changes in terrain or ecosystems that limit movement and provide a natural physical boundary to the environment as it is experienced, rather than a cartographic and possibly arbitrary border drawn on a map.

In this project, I interpret a bioregion as the habitat that I bodily occupy and move within as a space with physical limitations, borders that without mechanical vehicular assistance (such as an aircraft or a ship, for instance), I would be unable to pass. This region is the land I relate to as a lived, embodied space rather than a specific national and therefore political identity. It is fundamentally a geological, ecological and cultural space that I am part of and relate to as having multiple identities dependent on the constitution of the space and what I encounter within it. The shoreline itself is both the edge of two habitats, land and ocean, and a habitat in itself. For both human and non-human life, it can be both a site of pleasure and relaxation, and a site of danger and tragedy, as recent and ongoing events in the Mediterranean Sea, remind us.

Land~Edge considers the shoreline as a physical boundary that persists beyond humanity’s constructed borders and the resulting works are therefore interpretations of the bioregional edges of land, for as Lucy Lippard states; “Bioregionalism seems to me the most sensible, if least attainable, way of looking at the world.” The project has three parts; {1} The Search for Sisyphus, {2} The Fall and {3} Sisyphus Found.

Each work is a photo-collage with one image above and a composite human-scaled aerial view below. This method was devised to investigate and reflect on the nature of perceiving an edge; to move through it and be spatially, temporally and peripherally aware. The effect of these works is intended to be vertiginous to the viewer, as if on a precipice, as well as investigating themes of movement (across water in this case) with inferences to be drawn by the viewer through the subject matter depicted. The work is subtly geopolitical in this sense.

A paper was given at the conference alongside the exhibition.

Why Sisyphus?

I am not normally inclined to draw from the myths of classical antiquity for inspiration in my work, but in this case, an inference came unbidden from one of the works itself. Once piece, Fall, has a broken wing in it. To me, an obvious reference to the legend of Icarus.

It was not Icarus, but Sisyphus that interested me most, through the work of Albert Camus. In the Greek myth, Sisyphus is condemned to an eternity of pushing a boulder up a mountain. All day and every day he labours and each night the boulder tumbles back down. Each morning Sisyphus starts all over again, struggling to achieve his task with the full knowledge that it is impossible. In his philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), Camus states that far from being tortured by this he is, in fact, happy, his argument being that it is the striving toward the goal through the process, rather than in the achievement, that value lies.

Whilst I was undertaking this work, I found out that I had set myself an impossible task. I had decided to find the edge of land, the edge of my physical habitat, my bio-region. This seemingly simple undertaking revealed to me that accurately defining the edge of land for photography was almost impossible because this division between land and ocean, solid and liquid, is constantly in a state of flux, shifting with the tides and with each wave. Not only is this edge physically fluctuating, it is also culturally indistinct. Is the line on the map referring to high or low tide? Is it the edge of the shore or, for instance, the edge of the sand dunes or the top of a cliff? It could even be beyond the horizon, the boundary between national and international waters. Clearly the actual edge depends not only on (shifting) physical evidence, but also on a cultural perspective; a swimmer might identify land as the point when they can stand on the bottom, before leaving the water. A farmer might understand this edge as a field boundary.

Clearly there is no one single definition of this edge of land, dispite what it may appear to be on a map, hence this project is a search for Sisyphus, in which the process of the search for an edge, and its impossiblity, is a reflection on the nature of the edge itself as a constant flow of events continually defining and redefining this liminal space.

{2} The Fall

Liminality is often used to describe the edges of landscapes, like shores, as is the case here, or the space between the forest and the Savannah, for instance, but as Silvia Loeffler (2015) points out, it is also used to describe the threshold between the inner and the outer worlds, the inner psyche, and the outer environment it interacts with. In the Fall, I am deliberately projecting my own ideas and feelings onto the landscape through depiction. To do this I have changed my way of working, employing black and white film rather than the digital compositing techniques of The search for Sisyphus. Here, liminality is situated on the film surface, as the interface between myself, in the act of looking, and the light reflected from the land before me.

As with part one of Land~Edge, The Fall draws upon Albert Camus work in the book of the same title. Written in 1956, The Fall is the story of a lawyer’s decline into an uncaring cynicism, as narrated by himself in conversation at the latter stages of his life. This decline is triggered when he is walking across a bridge and passes a woman standing at the edge in a black dress. He knows she is in distress but does not approach her, continuing on. The woman jumps from the bridge and the lawyer walks on, ignoring her screams until she is silent. This apparent inability to care continues to intensify throughout his life.

This idea, of a kind of increasing lack of compassion, is reflected in contemporary global politics, of crisis in humanity, perhaps, due to a failing in political systems to deal with current problems and a sense of lack of agency in the voice of the individual. I find it difficult to articulate this feeling at this stage, but the metaphor of falling, and of the precipice and of decay and decline is what I am attempting to bring to this project in The Fall.

All works untitled.