I have for a long time held a fascination for the soils that are excavated on archaeological sites and considered how they might be used in my art practice. The Beaubec project (2019 – 2023) provided me with the perfect opportunity to investigate this through experimentation on an excavation.

As we dig, we analyse the soil, both in terms of what it can tell us about its deposition and, importantly, to recognise when one deposit, changes revealing another below it. These distinctions between deposits are not always clear and often changes are detected by touch rather than sight. A hand, through a trowel, may feel a rasping coarseness as a soft clay gives way to a gritty silt, although the colour may be very similar, an edge can be discerned that becomes clearer as careful intuitive movement follows this change and a feature is revealed. The skilled use of sensing through touch in archaeology is an important component of the craft of excavation, hence the title of this project, Touching time.

The work in this project is closely allied to the processes and craft of archaeology; of digging and recording the past through time to reflect on the act of excavation. I have used materials that are found on site as well as used in the recording process.

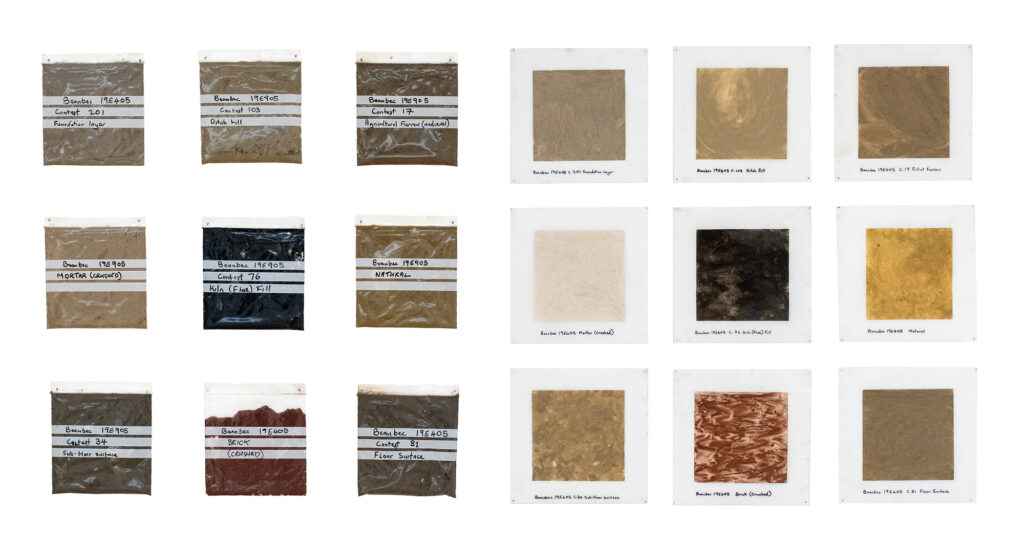

This includes the drafting paper that is used to cartographically map archaeology using pencil, as well as the actual soils themselves. There is no paint used here, all colour is derived from deposits discarded during excavation and reflect the pallet of Beaubec, as distinct from other sites and dependent not only on the natural geological deposits but also on the activities that took place here in antiquity.

Each context was used individually and often faithfully to their sequence of deposition, for instance I always start a work with a base layer of the beautiful brownish yellow glacial silty boulder clay. I would grind the soil in with a pestle and mortar adding water to make a paste, a pigment suitable to use on my drawings. I always used my hands directly on the works when dealing with the soil and never mix them, keeping faith with their different origins.

I have also used photography to record the process documenting the stages of the works on site, the various interactions between the materials and environment as they happened. Much of the work was undertaken in the outdoor environment of the excavation, and subject to changes in the weather, getting wet when it rained and cracking in the heat of the sun.

I view excavating as the closest we can get to time travel. As we dig down, we move through time backwards, experiencing the same materials in the same space as the people whose actions in the past resulted in these features being formed. It is in this way that I believe that excavating is, therefore, the best way to experience the past, and to imagine it as a result.

This project has been a valuable opportunity to investigate and develop a process that draws together art and archaeology from the complexity of a site into sight in the white space of a gallery and beyond.

The large wall drawing, The Great Barn, is based on the cartographic plan, or map, from the excavation and each soil is actually sourced from the feature depicted.

With thanks to the following for their assistance, collaboration, and encouragement; Penny Johnston, Matthew and Geraldine Stout, John and Grace McCullen, my gallery assistant Catherine Meehan, a whole host of enthusiastic volunteers on the excavation and the excellent team at Droichead Arts Centre.